The Matrix. A leading staple of cyberpunk spectacle that graced the way for a flurry of action genre tropes, as well as a wardrobe of shiny black leather and new metal headbangers of which every other noughties action movie partook. Yet, despite its exhausted aesthetic, its innumerable inadvertent memes and its seemingly shlock legacy, The Matrix remains an irreproducible triumph of action, style, tension and simmering ideological depth, while being super cool concurrently. It’s successors, however, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, haven’t managed to achieve the same degree of admiration. Excessively utilising action over substance, rendering exposition over-complex and force-feeding the viewer an existential philosophy that is both utterly convoluted and arguably nihilistic in practice.

Delving into each with no pretence over quality, this essay will attempt to decipher the thematic resonance of these films, the philosophical arguments denoted in their content and the eventual intended meaning of the trio. With a focus on concepts of free will, the quest for autonomy, the inevitable nature of destiny and narrative predestination, this essay will utilise only the confines of the cinematic trilogy, so as not to overload on complexities inherent when discussing the nature of existence.

Part One: What is The Matrix?

Released in 1999 under the writing and direction of the Wachowski sisters, Lilly and Lana, The Matrix depicts a dystopian setting in which our world is but a facade of the real. Society appears to exist as normal – people are seemingly in control, in-subservient and living of their own “free will” within a charred capitalistic wasteland of consumption and ignorance. The spoon-bending twist, however, is that of the Cartesian facade: that in fact, the world is false and humanity is living in a charred capitalistic wasteland of consumption and ignorance, albeit in this one, where we are the produce. A world where machines of our own making have learned to govern the existing (albeit broken) planet and utilise genetically grown human bodies to fuel their continued governance; tapping our neural cortex for battery power, while keeping us in check with the titular false reality.

We follow, Thomas A. Anderson or, Neo, as per his postmodern hacker alias. A self-isolated loner, living life day to day through his corporate job and the sickly green hue of his computer screen (sound familiar?). One night, after a tension-setting opening chase scene between Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) and three, as of yet, unnamed agents (the men in black). We find Neo, asleep at his computer, seemingly awoken at the behest of his monitor. “Wake up, neo…”, his computer screen reads, immediately underpinning the running theme of the film – to wake up, to realise the sham of societal coercion, of which the Matrix symbolises, and to break out from its cybernetic confines, move at one’s own pace and be the hero of one’s own destiny (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). To wake up, free and able to perform the most impossible of actions (dodging bullets, leaping tall buildings with a single bound, flying). To wake up autonomous, unshackled from the confines of reality – all mantras of a burgeoning subjectivity disguised in the film’s perpetual cultural references: an alarm clock, Alice in Wonderland, copious allusions to Zen Buddhism (Neo’s reflection in a bending spoon).

Incessantly dissatisfied and wasting away in a small, one room apartment, Neo struggles to maintain a monotonous programmer job at a respectable software company while selling cyber dope on the side to keep up his bubbling anti-establishment sensibilities. Restless with work and the conglomerate clutch of authority, Neo is aching to be free. His underlying want to bring down the established hierarchical control of systematic hegemony – the omniscient elite that govern all life from unknown heights – ubiquitous through his off-book cyber dealings and persistent lateness. A copy of Jean Baudrillard’s, Simulacra and Simulation, sat handily on his bookshelf, marked wittingly on the chapter, “On Nihilism”, further revealing Neo’s dissatisfaction with his current reality. Neo is acutely aware of the controlled stasis of his existence (and unconsciously of that of his want to be free).

Succinctly stated by Lisa Nakamura in her essay on The Multiplication of Difference in Post-Millennial Cyberpunk Film, the Matrix depicts “the uniformity of white male culture and equate it to machine culture” (Gillis 129). The simulation and the real form a coexisting uniformity resembling that of our real-world patriarchy. The machines as products of mankind and thus, the simulation as machine kind and therefore human (humans being the original creators of the machines). The “machine culture [of the Matrix] is viral, oppressive, assimilative”, governed by “white men, the agents” – inhuman replicas who embody the aforementioned uniformity of the simulation and thus, the real (Gillis 129)l. Men in suits, men with authority. White men who police the ongoing programmes in the Matrix, like the systems of governance that exist in our society. Those that maintain a culture of exploitation and coercion that is the same as in the Wachowski’s fictional simulation – subjects are trapped and tapped for their energy, bred for fuel and kept imprisoned within the bliss of their own ignorance. The Matrix is a hefty pseudonym for reality, expressing uniformity in ideals of employment and notions of capital. We are the symbolic subjects of the Matrix, governed by elitist structures of power, kept chained to societal constructs of coercion, lest we learn the truth of our subjugation. Neo knows he’s trapped, and thus subconsciously searches for a way out. His codename, his criminality, his anti-authoritarian persistence provide a semblance of an alter-ego – a self-governed, self-made identity of which his uniform society has failed to allow him thus. A guise of individuality, that of which is more real than society itself. Thomas Foster continues this discussion of controlled uniformity by acknowledging Neo’s subconscious want to be free. Writing in The Transparency of the Interface: Reality Hacking and Fantasies of Resistance, Foster notes that it is the “constraints placed on agency and free choice by the programming structures that characters [of the Matrix] must negotiate” (Gillis 62). A negotiation that Neo is on the cusp of attending. His self-purposed anagrammatic “One”, which incites New Age Messianic foreplay and presumptions of a Neoplatonic ideal, suggest Neo’s underlying awareness of his imprisonment and his capabilities beyond reality. While his birth name, Thomas Anderson, infers overtly to the religious figures of Jesus Christ (Anderson – “son of man”) and doubting Thomas. The former, a man who famously died for the freedom of all humankind, and the latter, one who at first is unwilling to believe in miracles. Neo, like Thomas, is attributed to his uniformity yet, like Christ, relays a brimming societal backlash through his criminality. He subconsciously sees himself as a new-age Messiah, while maintaining an inherent human doubt. He wants to be free. He just isn’t willing to believe it yet.

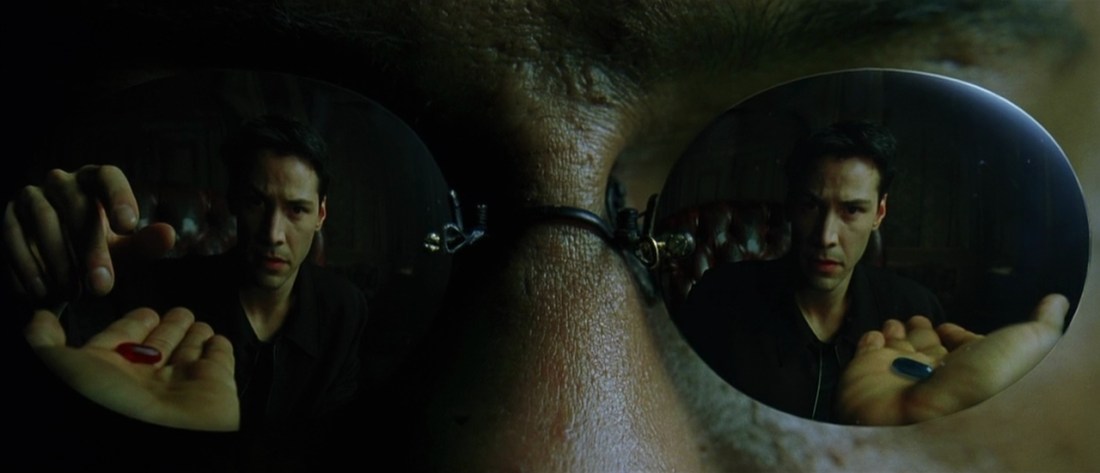

Although seemingly tied to his monotonous existence, Neo rejects the concept of destiny noting that he refuses to believe in fate as he doesn’t “like the idea that [he’s] not in control of [his] life” (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). This implies that he would rather see the world for what it is – a simulation, lines upon lines of code – an existential sandbox in which one would endeavour to form their own destiny. He would rather see the metaphorical code of existence, decode it and encode his own wants, dreams and desires – to explore the unknown bounds of individuality and imagination – instead to conform to the confines of pre-determinism. It takes the prodding epiphany of Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne) and the curious Trinity to help propel Neo into that unknown – the lawless underworld of reality. Neo must choose to face his own autonomy and break free of the chains shackled to him by the villainous monotony of life in the Matrix. To break free from the systems of capitalism that breed false wellbeing in money and goods – a job, a living, the sense of satisfaction that comes from being an obedient worker (a cog in the machine for cliché’s sake). Constructs that are stripped away by a man in leather whom appeals to the brimming sanctity of Neo’s subconscious knowledge that this is all fake and that he’s been searching for a way out the whole time:

What you know you can’t explain, but you feel it. You’ve felt it your entire life, that there’s something wrong with the world. You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. It is this feeling that has brought you to me. Do you know what I’m talking about? (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski).

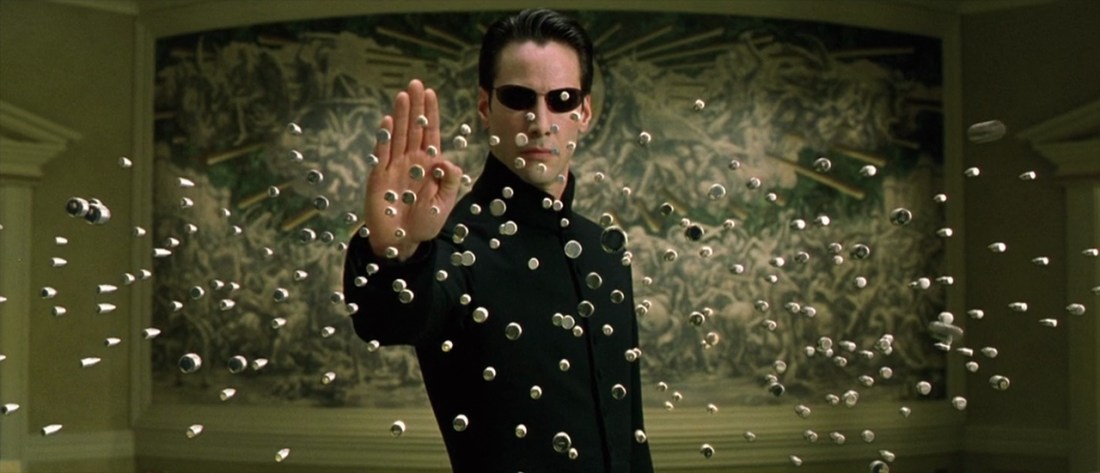

Morpheus, a man whose ideas seem ridiculous, as if asserted by an insane person. A radical. A terrorist. An extremist liberal labelled “the most dangerous man in the world” by Agent Smith, played lovingly by Hugo Weaving (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). A purposeful inference to another aspect of capitalist gain, to use the “radical’s language to achieve the conservative’s aim: the preservation of the capitalist system, and the traditional [..] hierarchy within society” as observed by American historian and critic, Manning Marable in 1979 (Peter Slade, 18). In The Matrix, the mechanical overlords use Morpheus’ seemingly extreme ideas to promote the wellbeing (and comfort) of capitalism and control. Yet, according to theorist, Noam Chomsky, speaking to Kevin Doyle in an interview for Red and Black Revolution magazine in 1995, “it makes sense to seek out and identify structures of authority, hierarchy and domination […] and to challenge them; unless a justification for them can be given, they are illegitimate, and should be dismantled, to increase the scope of human freedom” (Doyle). The machine’s culture of enslavement and subjugation prove their illegitimacy, their curtailment of human freedom, and therefore the need for their dismantlement. Moreover, the only justification for Neo’s life being to forward the consumption of produce for a conglomerate corporation of tyrannical machines endorse his subconscious challenge for autonomy. A facet that he is only beginning to realise. Neo is searching for the Matrix. His anti-authoritarian ideals, his hacking, his small-time criminal dealings all provide a semblance of challenge against conformity and provide the essence of libertarianism. He just needs to wake up, to realise his desires and confront the tyrannical forces of control. To see the truth with his own eyes and take back what is rightfully his – autonomy, free will and the right govern his own existence. During an interrogation scene, Agent Smith notes that Neo has “a problem with authority”, that he believes he is “special, that somehow the rules do not apply to [him]” (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). It is this thematic that keeps The Matrix as relevant and world-bending as it is today. Neo’s loner state and his want to find purpose and renounce systems of authority – those that by way of declaration have caused the catastrophic failure of humanity by creating machines and scorching the sky. He is utterly symbolic of millennial angst – wanting to help save the world but not knowing how to do so – thus, he complies to societal pressure while maintaining a degree of social deviance. It takes but a tumble down the rabbit hole and the suggestion of liberation to lead himself to freedom and the establishment of his identity.

However, this theme of freedom through liberation is contrary to the story in itself. Its Baudriallian assumptions of free will as holy grail exist only as precedent to enable Neo’s narrative escape from the Matrix, while allowing his so called “freedom” to be eclipsed by a larger, more inescapable fate. Neo is told to wake up and form his own destiny, only to let it slip into the jigsaw of predestination. He is predestined to break from the chains of the society and in doing so, become the ever-powerful “One”. The hero whom must destroy the tyrannical machines and free humanity from slavery. Neo’s fate lies within an inherent prophecy as Morpheus never fails to iterate: “You’re the One, Neo.” (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). Therefore, permitting the question, how can the dream of free will that drives The Matrix (and its subsequent sequels) formally take root? That the path of Neo is predetermined and therefore, exempt of free will, fundamentally contradicts the leading notion of the films. Lending more to the idea that, as humans, we deem to make our own decisions free from coercion and live life under our own jurisdiction only to yield to higher forms of control – fate and predestination. Existential concepts of which we have no power over. Thereby, making the entire effort of Neo (and that of the films) arguably without meaning or narrative precedence. That by way of the proclamation, humans are inherently stuck in an inescapable conflict of free will and predestination. Thus, mirroring the hegemonic cycle of imprisonment in which Neo initially intends to escape. A prison within a prison within a prison, of which, the only visible way out, is to succumb to these structures of domination and employ an air of ignorant bliss – a problematic thought in an industry which generally covets box office sales over artistic freedom.

Part Two: Contradiction Reloaded

In the series’ subsequent additions, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions (both released in 2003), the paradoxical theme of attaining free will, while submitting to the inevitability of predestination concurrently, is presented exhaustively. Unfortunately for the viewer, these films fail to garner the complex depth and style of the original film. Predisposing action over substance and losing story to over-complicated dialogue, an abundance of glamorous yet shallow set pieces and additional supporting characters that lack the depth of Trinity and Morpheus. However, despite these failings, they do succeed in continuing the exploration of its central character, his muddled autonomy and eternal quest for free will, albeit with a lesser degree of clarity than their iconic predecessor.

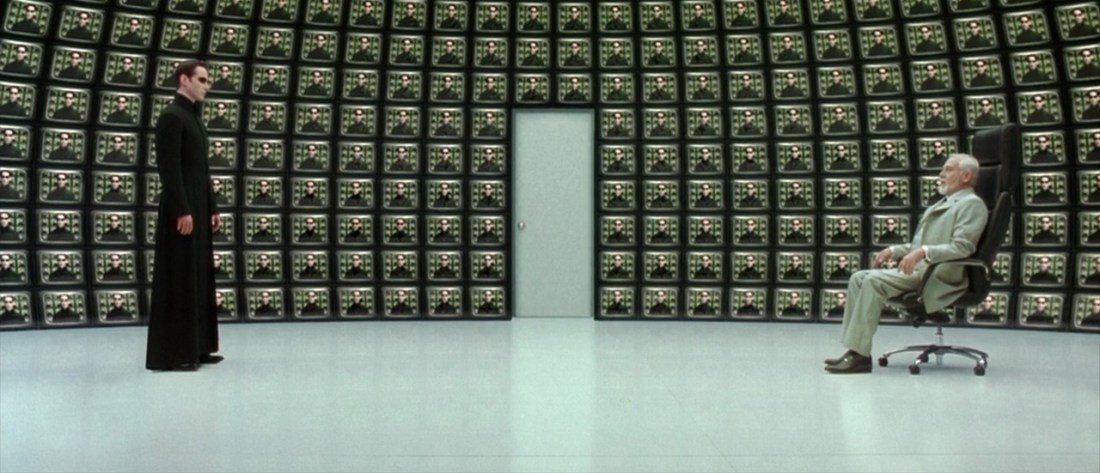

In Reloaded, during a guns-blazing heist to get Neo into the source of the Matrix, the central computing core for the entire Machine mainframe, in order to repel an attack on Zion (the last human city) by the tyrannical machines, he instead stumbles upon the maker of all things. The Architect, the creator of the Matrix and the symbolic father of its subjects (the mother being the all-seeing, cookie-baking, Oracle). A godlike programme in the form of an old man surrounded by television screens that, while overtly infer the video surveillant, omniscient rule of the machines, directly reference Korean artist, Nam June Paik’s, 1971 TV Eyeglasses installation – a wall of television screens set to explore the coexistence of humanity and technology. The emerging merging of the technological with the organic – “The television screen [as] the retina of the mind’s eye” to quote David Cronenberg’s, Videodrome. The machines are one with humanity, as inferred by the panoptic array of television screens, forming a symbiotic relationship of coercion and dominance. Humanity – grown and absorbed of its life force, as to fuel Machine existence, while living comfortably in a simulation, ignorant to the degree of oppression in which they exist. The dead, liquified and fed intravenously to the living so as to sustain this unnatural symbiosis of technology and flesh. Constructs of living – free will, civilization, identity – are rendered allusions sold to permit the continuation of Machine-kind.

Furthermore, the Architect reveals that Neo’s messianic “Oneness” is merely a part of a larger whole and attributed to him merely as per the result of an ongoing troubleshoot within programmes. Neo is but one “One” of six iterations of “One”. He is a glitch, an anomalous eventuality, “the sum of a remainder of an unbalanced equation inherent to the programming of the Matrix” of which the Architect has been unable to be eliminate from what is otherwise “a harmony of Mathematical precision” (The Matrix Reloaded, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). An anomaly which is systemic and caused emphatically by the question of choice. Neo is given the option to either enter the source and restart the Matrix, so as to ensure the continuation of the human race, while allowing the destruction of his friends in Zion (as every instance of his predecessor has chosen) or to bust out of the room and save Trinity, the one he loves and whom is doomed to die as collateral of the aforementioned heist. As foretold by the Architect:

The function of the One is now to return to the Source, allowing a temporary dissemination of the code you carry, reinserting the prime program. After which, you will be required to select, from the Matrix, 23 individuals – 16 female, 7 male – to rebuild Zion. Failure to comply with this process will result in a cataclysmic system crash, killing everyone connected to the Matrix, which, coupled with the extermination of Zion, will ultimately result in the extinction of the entire human race.

Neo’s messianic path permits that he choose the human race over Zion (and Trinity), his predetermined existence as a “prime program” with a “profund attachment to the rest of [his] species” insists that he reset the Matrix and allow this cycle of destruction to continue perennially (The Matrix Reloaded, Lilly and Lana Wachowski).

Yet, the difference between Neo and the other messianic “Ones” is that he has the ability to love, or more precisely, that his feelings toward Trinity forgo his predestined nature to preserve humanity and restart the Matrix. The Architect explains that:

[Neo’s] 5 predecessors were, by design, based on a similar predication – a contingent affirmation that was meant to create a profound attachment to the rest of your species, facilitating the function of the One. While the others experienced this in a very general way, your experience is far more specific – vis a vis love. (The Matrix Reloaded, Lilly and Lana Wachowski).

Neo’s love enables his capacity to choose. His love gifts him a semblance of autonomy, while subsequently rendering the whole concept of free will far more complex. By the Architect’s proclamation, Neo is predestined to reach this point in the narrative, to reset the Matrix and to allow a systematic repeat of the same events in order for the maker to continue perfecting an imperfect programme. Yet, instead Neo finds himself governed by his feelings towards another, Trinity. Stacy Gillis, editor of The Matrix Trilogy: Cyberpunk Reloaded, insists that the Matrix trilogy is “actually Trinity’s story […as] she is the catalyst for all action […] both the ass-kicking cyberpunk and the femme fatale” (Gillis 74). This couldn’t be more pertinent than in this very scene, where Neo’s “free will” is dominated by his love for Trinity. Her seemingly inevitable death – falling from a burning skyscraper of her own making, with a bullet wound in her gut – is the catalyst for Neo’s choice. Although predetermined to ensure the continuation of the human race (by way of resetting the Matrix), Neo instead chooses love – favouring emotional attachment over the assured continuation of his species. Dana Dragunoiu writes in Neo’s Kantian Choice: “The Matrix Reloaded” and the Limits of the Posthuman, that “Neo’s confrontation with the Architect illustrates how choice can be made to function as a mechanism of control” (53). Neo is given the ultimate decision to either save humanity from utter annihilation or to save his beloved. Yet, each of these coercions have been constructed by programmes of the Matrix. As revealed by Trinity in climax of the first film, Neo’s love for her is spurred on by the Oracle’s prophecy “that [she] would fall in love, and that man, the man who [she] loved would be the One”, while his preordained “Oneness”, that permits he will save humanity, is, as declared by the Architect, the sum of an unbalanced equation inherent to the programming of the Matrix (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). Ergo, Neo is destined to be the hero of legend and thereby destined to fall in love with Trinity – a love which indirectly influences his actions accordingly (choosing her over thus hindering his function as “the One”).

This begs the question, is Neo ever fully autonomous? With either a convoluted systematic predestination or the safety of his beloved to choose from, is Neo ever capable of making a decision purely out of free will, or is he destined to make choices forever coerced by emotion and/or logic? The answer is tricky and arguably inexplicable but I believe the Wachowski’s litany is something akin to the following: that as humans, it is our ability to love that frees us from the machine-like tentacles of systematic control. Whether those that erect from the governance of a hegemonic capitalism or quite literally, the metallic grip of the Machines in The Matrix series. Love is what nurtures free will – allowing us to make decisions purely on an emotional level. Trinity is going to die. Neo has the ability (and the desire) to stop this, and thus, he does, and in great cinematic style – exploding out of the Architect’s televisual panopticon and flying at the speed of sound in order to save his beloved at the very last second. Neo chooses emotion over reason. Desire over logic. Free will over predestination. However, this prospect is made inarguably complex by the notion that Neo was destined to meet Trinity. That by prophecy, as told by the Oracle, he was predestined to fall in love with her, and thus, by fate, to choose her over the human race. Thereby, debunking the entire concept of free will as but another aspect of the Matrix’s imperfect programming. A cybernetic law presiding over all love, logic and liberty.

Part Three: Compounded Revolutions

In the third entry of the saga, The Matrix Revolutions, all presiding themes of free-will-as-grail and love-over-logic are lost amidst a slew of action scenes and an overabundance of philosophical exposition that leave the viewer more lost than after Neo’s existential discourse with the Architect in the film prior (or after this essay for that matter). Yet, the final sequence of the film does make an attempt at returning focus back to these thematics, if only to succumb to contradictory storytelling in Neo’s final words.

Over the course of the final film, Neo has died, been revived, lost Trinity and has made his way back to his proverbial place of birth – the Machine City. The place where all human life continues to be governed and grown by its machine overlords, and the place where Neo must negotiate the continuation of his species while the remaining humans battle leagues of Sentinels in the depths below in the final Battle of Zion – the climax of the perennial First Machine war as per the Matrix Wiki (just think mechs and guns and a light show of lasers). Neo enters into discussion with the very anime-esque face of the machines, whose physicalization is formed from the bodies of hundreds of lesser automata. A complacent metaphor for the hegemonic structures of power of which the in and within the Matrix – machines building machines, cogs within cogs. The two powers that be discuss the prescient issue at hand, the ironic nature of their final conflict, that they must now work together to establish agency and freedom from the parasitic dominance of Agent Smith. The programme once destroyed by Neo (at the end of The Matrix) has become undone – made out of control by his ineptitude and his search for a way out. Due to Neo’s killing of him, Smith has been subsequently freed from his programming by way of exile. As per the rules of the Matrix, he can either continue as a malfunctioning programme or submit to deletion by the source as explained by the Oracle in Reloaded: when a programme “breaks down[, …] a better program is created to replace it; happens all the time. And when it does, a program could either choose to hide here… or return to the source” (Lilly and Lana Wachowski). Churned by the notion of his obsoleteness, Smith’s megalomania spurs him to deny his deletion and instead, corrupt all other programmes within the Matrix. He forcefully assimilates with seemingly every programme within the simulation and reproduces copies of himself, multiplying a thousand-fold in a desperate attempt to escape from the confines of this cybernetic shell. Thereby, creating an army of Smiths intent on killing and succeeding both machine and humankind in tandem. And since only Neo has the power to stop him, the Machine’s hear his plea and allow him to enter the Matrix once more through its central nervous, the aforementioned “source” that all malfunctioning programmes must return, if only to stop the parasitic Smith from ending machine-kind, while their remaining sentinels continue to barrage the human city of Zion.

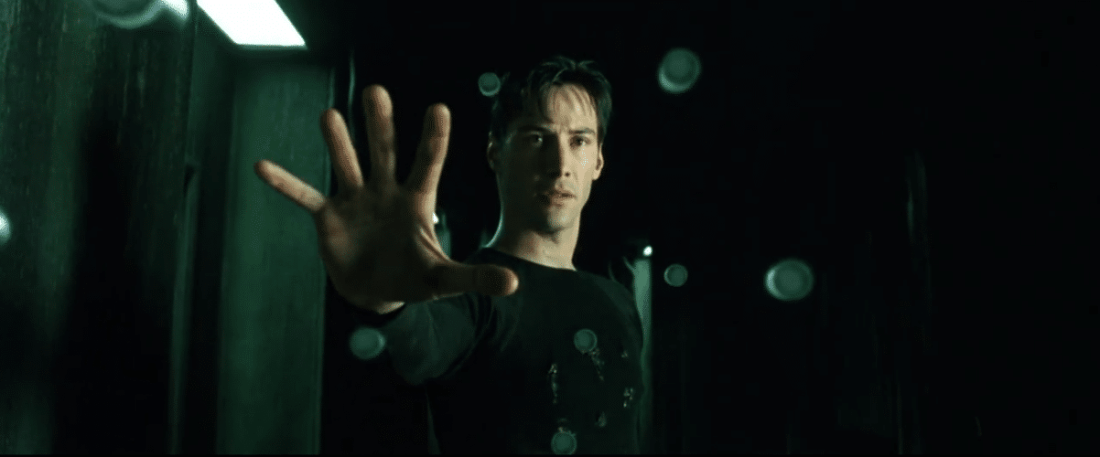

Neo enters and stands amidst rain and lightning, aligned by countless Smith clones while the original stands opposite, goading our hero with his prophetic notions of victory. Neo insists that “it ends here”, to which Smith responds, “I know it does, I’ve seen it. That’s why the rest of me is just going to enjoy the show as we already know that I’m the one that beats you” (The Matrix Revolutions, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). Smith believes it “inevitable” that he will assume form with Neo as he has for every other programme in the Matrix. That he will escape from this cyber prison and wreak havoc on the chaotic world, ridding it of what he describes as “a disease, cancer of this planet” – humanity and all its undoings (The Matrix, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). This is partly due to his assimilation with the Oracle’s body earlier in the film, which thus gives him the ability to see the future and derive that he will be the victor in this overly epic (and wet) climactic fight. Knowing full well the inevitability of the battle, Neo fights him nonetheless, thus ensuing the most anime-esque (and seizure-inducing) spectacle of the franchise. Bodies fly, lighting strikes and great feats of superhuman martial arts are interspersed with superlative dialogue that feels straight out of Dragon Ball Z. Near its end, Smith stands above his opponent recounting his distaste for the human race and their never-ending fight for a seemingly inconceivable objective:

Is it freedom or truth, perhaps peace, could it be for love? Illusions, Mr Anderson, vagaries of perception. Temporary constructs of a feeble human intellect trying desperately to justify an existence that is without meaning or purpose, and all of them as artificial as the Matrix itself (The Matrix Revolutions, the Wachowski siblings).

Yes, after all this discussion of free will and love, Smith cuts in with a nihilist eradication of everything Neo, everything humanity, has fought for. That every aspect of the human psyche – love, peace, free will etc. – is but a construct “to justify an existence that is without meaning and without purpose”. That every motive, every passion, every soul-defining reason to exist is but an aspect of an inescapable truth that we are slaves to the constraints of fate and predetermination. Helpless and futile to the powers that be… And yet, Neo still fights. Disregarding his opponent’s victorious knowledge and instead revealing the reason that he chooses to fight is not for love, nor for freedom, peace or truth. It is for choice itself. Neo fights for the sole, freedom-defining, truth-upholding, love-ensuing, peace-revering virtue that he “choose[s] to” (The Matrix Revolutions, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). As noted by Russel Kilbourn in Re-Reading “Reality”: Reading The Matrix, Neo is confronted by “choices structuring the narrative […that] individual choices and something like an overriding “fate” appear to be two sides of the same coin – “fate” being the pseudonym of narrative inevitability” (45). Neo fights for choice, Neo is given freedom of choice, and Neo will win by submitting to narrative inevitability. Kilbourn continues that Neo must be “presented with the semblance of a choice [… if he] is going to realize his potential of “the One”” (46). Throughout these films Neo is given this semblance of choice and his journey follows thusly. By allowing himself to become “the One”, in order to free his people, destroy Smith and end this cycle of hegemonic tyranny, Neo fights for a choice which he is already predestined to choose. Thereby succumbing to a paradoxical merging of both free will and fate – one that makes his eternal fight for autonomy meaningless, as even in the most climactic of choices, he is still fatefully destined to choose. This is so perplexingly contradictory that it makes the entire thematic of the trilogy excruciatingly bewildering and considerably problematic from a socio-political point of view. Neo is destined to search for a goal which is ultimately unobtainable, a construct of a construct of a construct. A false sense of control that Dragunoiu writes is “designed to mislead [humanity] into thinking that their lives [are] guided by choice” (53). An inescapably nihilist approach that permits that even the concept of free will in The Matrix is meaningless, and that by searching for it, Neo is simply yielding to the contradiction of his creation.

Additionally, what’s even more perplexing is that Neo is aware of this contradiction. His final line, after his admission of choice, is the utterance that “[Smith was] right. [Smith was] always right. It was inevitable” (The Matrix Revolutions, Lilly and Lana Wachowski). Thereby, admitting that he knows and understands the inevitability of his choices, and that, although he fights for freedom and autonomy, his will is governed by his destiny to choose. Thus, exposing what Kilbourn describes as the trilogy’s “central thematic paradox replicated on a formal level” (45). Freedom of choice is but an inevitability of the programming of the Matrix, which, as a reflection of life itself, infers that the human-made constructs of reality – love, logic, truth, violence, peace – are illusions that by way of free will, we endure. Whether that means that all choice is governed by a higher power is unclear, but it does determine that our power to make decisions is decided by our irreconcilable subjugation to our uncontrollable emotions. Thereby, alluding to the prospect that although free will is governed by emotion, emotions are ungovernable – our feelings towards each other, to our planet, to our existence are uncontrollable, and therefore, our reactions (our modes of free will) are too.

Smith wins, assimilates with Neo and yet, dies. And since Neo is connected to the aforementioned source, Smith is subsequently connected thusly, making his victory over Neo inevitable, and therefore, his deletion, inevitable also – an inevitability governed by choice, governed by emotion, governed by Neo. Thereby, cementing the final conflict of the film, while leaving the climax uncertain. Are we as humans capable of free will? If our decisions are governed by the overriding oppression of emotion, then how can we truly make autonomous choices regardless of feeling and bias? And if our emotions are governed by a predetermined, existential path, then how can we know if our choices are determined by free will or by that of a higher power? The answer is unclear, and perhaps that’s okay. Maybe it’s better to make choices governed by feeling rather than be the complacent machines that render all life meaningless and futile. Better to exist to love and be governed by love than to exist just for the point of existing.

The Matrix: Conclusions

The Matrix films stand as a pinnacle of the cyberpunk genre. While arguably incomparable in terms of quality, they succeed in reaching complexities of existential terror that are beyond the capable understanding of general audiences. Although labyrinthian in plot, the attempt to bring to surface the myriad questions that surround the concepts of free will and predestination is by and by the most admirable facet of these films. Questions of autonomy, love, emotion, destiny and creation are all but various colours splashed unabashedly on the canvas of the Wachowskis’ revolutionary attempt at bringing complex, anime-inspired, sci-fi action to the forefront of western cinema. The fact that these movies combined have grossed over $1.5 billion collectively is in itself an achievement, especially when compared to many previous science fiction endeavours, which largely failed to find their true audience until years after their release (The Thing [1982], Blade Runner, Silent Running). Unfortunately, the latter two films in The Matrix series struggle to maintain the quality of the original, favouring an over abundance of action to douse a near-inaccessible plot. Reloaded and Revolutions strive to present an excruciatingly complex philosophy that, although laudable in concept, generally fails to ensure the equilibrium between discourse and kung fu. While their predecessor, The Matrix, succeeds in presenting a perfect balance of cool and clever. Its choreography – smooth and explosive. Its dialogue – concise and exhilarating. Every aspect of the film is over-the-top, bordering silly, and seemingly trying to hit every action sci-fi movie staple. The cool one liner, the exploding helicopter, the deep, meaningful, exposition-heavy reason for why the world is ending (or has ended in this case). Yet, the film never feels bogged-down in these troupes. Everything feels earned and significant. From the pseudo-punk gothic attire to the Y2K music that should arguably cement this film within its contemporary. The Matrix lives on through thematic resonance, a committed style and sound, and a hype-building third act which pits a multiple guns-toting Neo and Trinity against a slew of guards and agents in their attempt to save Morpheus and in turn, the world. Amidst a slew of irrelevancy-inducing memes, this movie stands strong, asserting its dominance above the rest and maintaining its impact far beyond its release. It’s a shame that the sequels couldn’t live up to its excellence. Maybe the upcoming fourth edition will succeed in their stead.

References:

Cronenberg, David, director. Videodrome. Criterion Collection, 2010.

Doyle, Kevin. “Noam Chomsky on Anarchism, Marxism & Hope for the Future.” Noam Chomsky on Anarchism, Marxism & Hope for the Future, http://www.ditext.com/chomsky/may1995.html.

DRAGUNOIU, DANA. “Neo’s Kantian Choice: ‘The Matrix Reloaded’ and the Limits of the Posthuman.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, vol. 40, no. 4, 2007, pp. 51–67. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44030393. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Gillis, Stacy. The Matrix Trilogy: Cyberpunk Reloaded. Wallflower Press, 2005.

KILBOURN, RUSSELL J.A. “RE-WRITING ‘REALITY’: READING ‘THE MATRIX.’” Revue Canadienne D’Études Cinématographiques / Canadian Journal of Film Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 2000, pp. 43–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24402660. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Slade, Peter. Mobilizing for the Common Good. The Lived Theology of John M. Perkins. University Press of Mississippi, 2013.

Wachowski, Lilly and Lana Wachowski, directors. The Matrix. Warner Home Video, 1999.

Wachowski, Lilly and Lana Wachowski, directors. The Matrix Reloaded. Warner Home Video (UK), 2003.

Wachowski, Lilly and Lana Wachowski, directors. The Matrix Revolutions. Warner Home Video (UK), 2004.